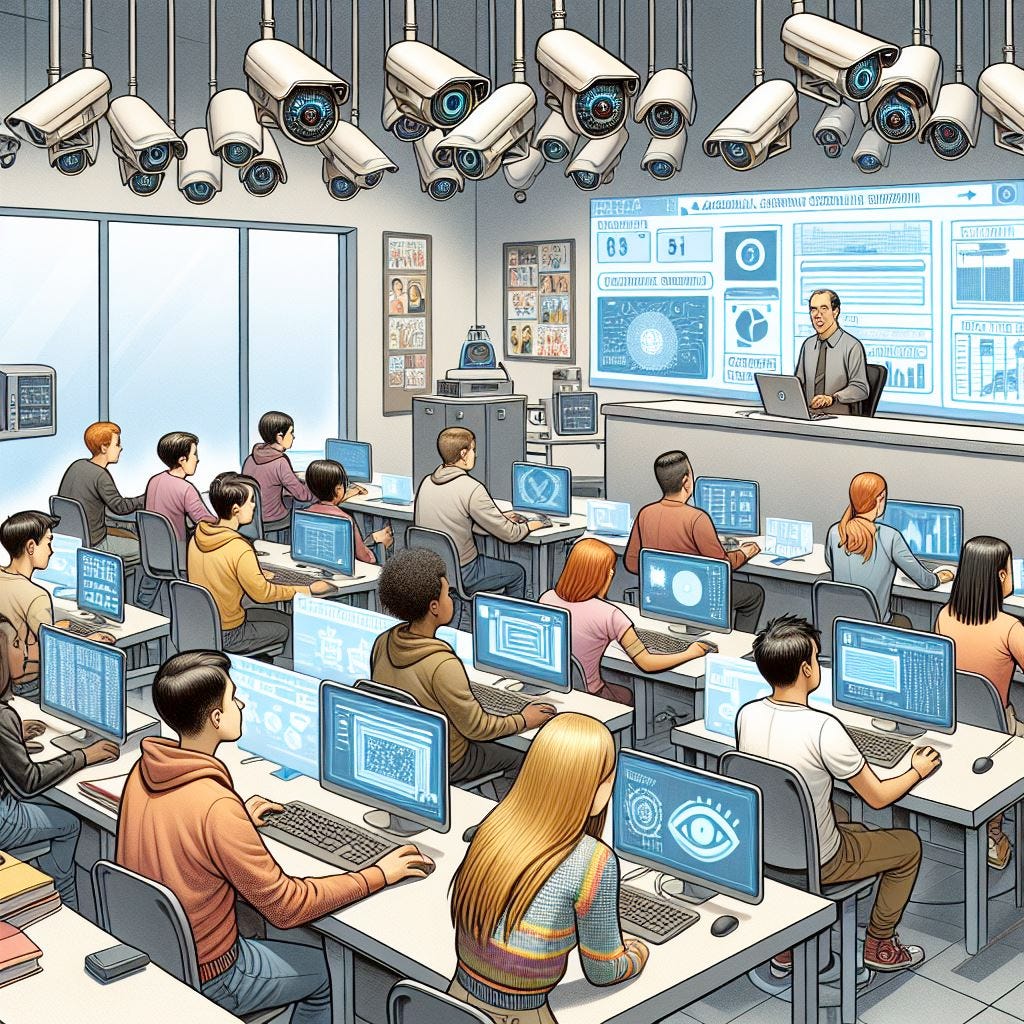

For decades, educators have grappled with the issue of academic dishonesty, often responding by implementing surveillance and enforcement measures: proctoring exams, locking down browsers, employing plagiarism checkers, and now using tools to detect AI-generated writing. While academic integrity is undoubtedly important—and as anyone who has worked with me can attest, I am a fierce advocate for it—it’s worth asking: Have we become so preoccupied with preventing cheating that we’ve lost sight of our mission to teach? Have we allowed the impulse to police students to overshadow our role as educators?

GenAI and the Fear of Cheating

The arrival of ChatGPT and similar generative AI (GenAI) technologies reignited longstanding concerns about academic dishonesty. The initial reaction across faculty forums, listservs, webinars, and conferences often centered on one idea: students would use these technologies to cheat. This fear has dominated discussions about AI in education, creating a pervasive narrative of mistrust.

As Gavin P. Johnson points out, such discourse frames students as “purposely deceitful and mercilessly unethical,” fostering a culture of suspicion that undermines the learning environment. Instead of viewing student writing as an opportunity for engagement and feedback, faculty often filter that writing through plagiarism and AI detection tools. If a tool flags a piece as potentially AI-generated, the assumption is guilt—leading to punitive actions rather than meaningful pedagogical interventions.

The Ethical and Equity Issues with AI Detection Tools

Ironically, while educators critique GenAI technologies for their ethical problems, many have embraced AI detection tools without equal scrutiny. These tools are not only expensive and error-prone but also raise significant equity concerns. Despite these issues, institutions have readily adopted AI detection tools, embedding them into systems like Canvas and offering limited opt-out options. This widespread acceptance reflects a troubling willingness to prioritize surveillance over critical reflection on teaching and assessment practices.

Policing Is Not Pedagogy (Thanks, Gavin Johnson)

When the COVID-19 pandemic forced education online, similar fears about skyrocketing academic dishonesty emerged (see Lindsey Albracht and Amy J. Wan’s “Beyond “Bad” Cops”). Yet, instead of addressing these challenges through rethinking pedagogy, many educators turned to surveillance tools. This response reveals a pattern: when faced with changes that challenge traditional teaching methods and assessment practices, the instinct is often to double down on policing rather than reimagine how we teach, assess, and engage students.

In a recently published conversation among literacy educators, one educator noted, GenAI technologies compel us to rethink our definitions of learning and writing. Another suggested that the resistance to AI stems from its ability to expose the limitations of conventional essay-based assignments—assignments that AI can now easily replicate.

Rather than perceiving these changes as threats, we should view them as opportunities to evolve our pedagogy. Engaging students in conversations about writing, critical thinking, and the ethical use of AI can foster deeper learning and reduce the reliance on punitive measures.

A Balanced Policy on AI Detection Tools

At my university, a newly available AI detection tool integrated into our learning management system with no option to opt out caused a wave of panic among instructors. Emails poured in: “The report says this essay was 100% AI-generated. Should I file an academic integrity case?”

In response, I worked on a research-informed policy for the writing program addressing the use of AI detection tools. I drafted this policy, seeking to provide clear guidance while discouraging reliance on such tools. The policy1 does not forbid their use but encourages instructors to consider the limitations and ethical implications of these tools before relying on them. It prioritizes pedagogy and student learning over surveillance and punitive measures.

As more research on the flaws of AI detection tools becomes available, I will continue to update the policy to reflect current knowledge and resources. My goal remains the same: to support instructors in making thoughtful, informed choices and to shift the focus back to teaching and learning.

Moving Forward

The rise of GenAI technologies challenges us to reconsider not only how we teach but also how we build trust and engagement in our classrooms. Policing is not pedagogy, and surveillance is not teaching. As educators, our responsibility is to create environments that prioritize learning, curiosity, and critical thinking. By resisting the urge to default to detection and punishment, we can embrace a more thoughtful and transformative approach to teaching in the age of AI.

Feel free to share this policy and to use with attribution.